National capitals are places where people come from all over the country to pursue their ambition. That makes them very gay places. Away from the prying eyes of hometown snoops, those who would be politicians, ambassadors, bureaucrats and activists can explore sides of themselves they might otherwise keep closeted.

In his fascinating book Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington, published last year by Macmillan, journalist and author James Kirchick makes a case that the United States capital is the queerest of them all. Gay sex scandals knocked several administrations sideways. Even as homosexuals were demonized by the government—during the era of Nazi power in Germany they were thought to be prone to fascism, then later thought to be prone to communism and so never to be trusted—they ran the very town where government lived.

We asked Kirchick, who moved to Washington from Boston about 15 years ago, for a quick tour around the federal district. He told us about places to visit which are jam-packed with LGBTQ2S+ history—and a few places to go just for fun.

Lafayette Square (Pennsylvania Ave. NW and 16th St. NW, Washington, D.C.).

From the 19th century to the 1950s, this well-manicured park, directly across from the White House, was the city’s main gay cruising ground. “There are police reports from the late 19th century about men being arrested for seeking out sexual encounters. It says a lot about Washington that this place across from the home of the most powerful man in the world is also the place where these secret citizens are meeting one another at night,” says Kirchick. After police crackdowns in the 1950s during the Lavender Scare, when LGBTQ2S+ people were seen as a national security threat and purged from government jobs, the cruising moved north to Dupont Circle.

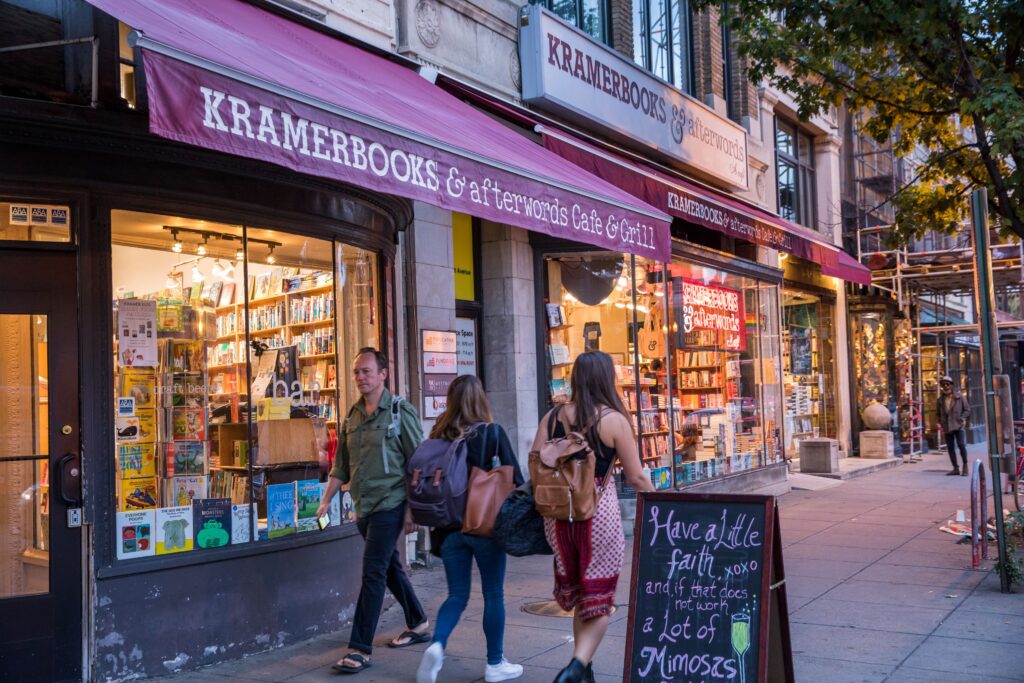

Dupont Circle.

What had been an affluent Black neighbourhood in the early 20th century became hallowed out during the racial strife of the 1960s, says Kirchick. Enter gay men with a bent for gentrification. Nicknamed the Fruit Loop, this became the city’s most visible gay district and was home to the late Lambda Rising bookstore from 1984 to 2010. These days, like many gay villages, Dupont Circle isn’t as gay as it used to be, but there are rainbow flags along 17th, as well as long-time easy-going fave JR’s Bar. Kirchick points out that even after segregation legally ended in the U.S. in 1964, the city continued to be socially segregated; bouncers at white-oriented Washington gay bars used to ask Black men for two pieces of ID or prohibit certain clothing items popular among Black men in order to deny them entry. So Black bars were more likely to pop up in other spots around the city, like current popular spot Nellie’s Sports Bar on U Street. This also explains why D.C. has Black Pride in May, as well as Capital Pride, centred on Dupont Circle, in June. Washington will host WorldPride in 2025.

Trade (1410 14th St. NW, Washington, D.C.).

Although there are several one-off dance parties around the city, Kirchick says Trade, though small, is the closest thing to a dance club these days. It features drag shows and other special events, as well as generous happy-hour drinks.

Congressional Cemetery (1801 E St. SE, Washington, DC).

This is the burial place of J. Edgar Hoover (1895–1972), a (most likely) gay man who, serving as the first director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), persecuted homosexuals, Black people and communists. But that’s not the reason to visit the cemetery. Nearby Hoover’s plot is the grave of Leonard Matlovich (1943–1988), a Vietnam War veteran who was the first openly gay soldier to challenge the U.S. military’s ban on gay and lesbian people. “When Matlovich died, he wanted to create a memorial for gay people and he chose a plot as close as he could get to Hoover’s as basically a ‘fuck you’ to Hoover. Then all these other gay people started buying up plots in the area, so you now have this gay corner of the Congressional Cemetery,” says Kirchick. “Malovich’s is very moving. He has a phrase on the headstone: ‘When I was in the military, they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one.’”

National Mall.

The grassy mall is not only home to the city’s major monuments and museums—the Lincoln Memorial at the west end, the United States Capitol at the east—it’s also where major marches advancing LGBTQ2S+ rights have been held, starting with the first National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, held on October 14, 1979, a protest spurred in part by the assassination of openly gay California politician Harvey Milk. Subsequent marches in 1986 (300,000 participants) and 1993 (more than a million participants) drew further attention to the movement. The AIDS Memorial Quilt was displayed here for the first time on October 11, 1987, and was displayed in its entirety for the last time in 1996 when, having grown in size, it covered the entire National Mall.

P Street Beach (1414 22nd St NW #7, Washington, DC).

Not a beach at all, it’s a grassy area along Rock Creek that’s been a gay hangout. “Sunbathing would go on there in the 1980s, and there was a cruising ground nearby they called the Black Forest,” says Kirchick.

Annie’s Paramount Steakhouse (1609 17th St. NW, Washington, DC).

Though the food is just so-so, says Kirchick, this Dupont Circle restaurant is famous for a story that dates back to the 1970s. The eponymous proprietor saw two men holding hands under the table. Looking annoyed, she went up to them and told them “you don’t have to hide that here” and indicated they should hold hands on top of the table. It’s become a must-visit for many LGBTQ2S+ visitors to Washington.

The White House (1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington, DC).

If you’re visiting Washington, you’re inevitably going to end up here, but one interesting queer tidbit to help inform your visit was an event in March 1977 when, for the first time, gay and lesbian activists were invited to the White House to discuss their grievances about discriminatory federal policies with then-president Jimmy Carter. According to Kirchick, the meeting helped contribute to the anti-gay backlash of the time, personified by singer Anita Bryant. “She cited that meeting being an example of the moral rot in Washington,” he says.

Mayflower Hotel (1127 Connecticut Ave. NW, Washington, DC).

This landmark hotel, opened in 1925 and now part of Marriott’s Autograph Collection, has many gay stories to tell. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover would lunch here every day with Clyde Tolson, his protégé and suspected lover, says Kirchick. In the early 20th century, the hotel’s bar appealed to a mixed crowd and gay men and lesbians, and it’s still walking distance from Dupont Circle and Logan Circle nightlife.