Jan Morris was already one of the English-speaking world’s most famous, and most beloved, travel writers when she transitioned in the early 1970s. Born in Somerset, England, in 1926, and starting her writing career in the 1950s, she produced more than 50 beautifully written books—landmark works about Oxford, Venice, Trieste, Hong Kong and New York City, as well as several memoirs including 1974’s Conundrum, about her experiences with hormone treatment and gender-affirmation surgery.

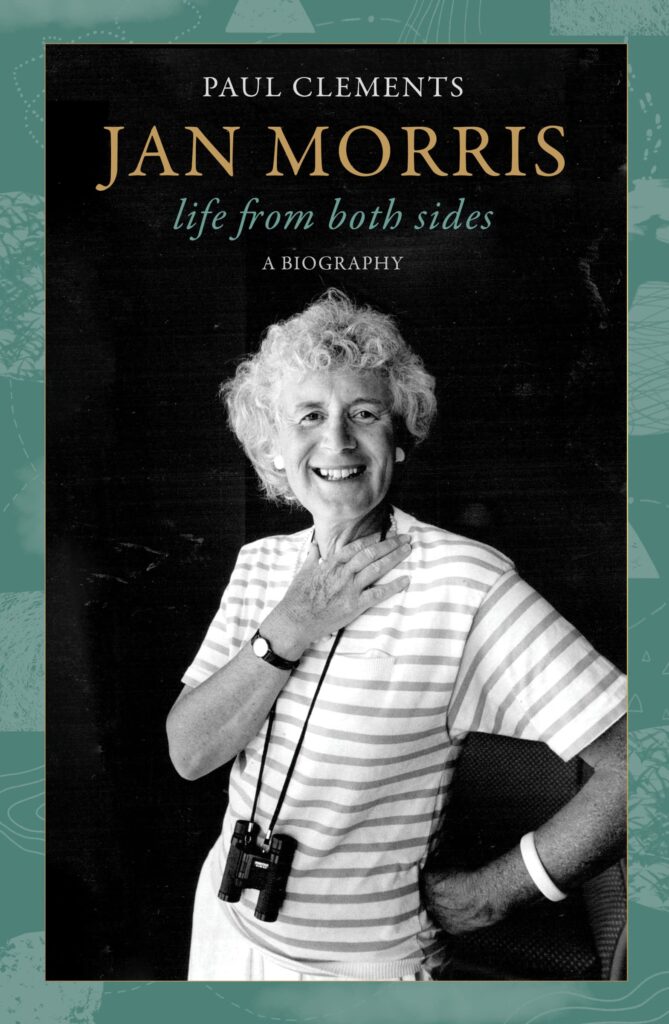

Her life story was as compelling as the stories she wrote. A biography by journalist and broadcaster Paul Clements, Jan Morris: Life from Both Sides, was published late last year, just two years after Morris’s death in 2020 at age 94. The compelling book chronicles her military service, her career as a foreign correspondent, her career as a travel writer, her transition and her long life in Wales with her wife Elizabeth.

We went through Clements’ biography looking for life and travel lessons that LGBTQ2S+ travellers might learn from Morris. Here are a few insights we found.

1.

In 1953, Morris was the only journalist, a correspondent for The Times, to join the first ascent of Mount Everest. Morris did not let the tough conditions of the trek discourage her from making history: “I am in a filthy state, like everyone else. I badly need a clean shirt, my nails are dirty and broken; my beard has just reached the state of looking intentional, my old shoes are beginning to crack; my hair is too long and needs a good wash… The most unpleasant part about it, to my mind, is the breathlessness that overcomes one. One pants at the slightest exertion, such as tying a shoelace.”

2.

You need to listen to a destination just as much as you need to look at it. At age 33, Morris and Elizabeth spent six months living in a top-floor flat in a palazzo in Venice, a room with a view of the Grand Canal. Morris used small black notebooks to record “background colour, fleeting moments that would otherwise be forgotten by visitors. She captured the city’s sounds—the readers of Venice [published in 1960] can hear the city’s onomatopoeic plop, splash, hiss and fizz, the click of high heels or the floating voice of an operatic contralto,” writes Clements. “Morris found it disconcerting to hear snatches of conversation while meandering home late at night, suddenly realizing how far and how loudly the sound carries along the canals. A quieter mood hangs over her descriptions of strolling through the streets at night.”

3.

Honesty matters in both writing and in relationships. Towards the end of the 1950s, Morris considered starting hormone treatments to deal with her questions around gender, deciding to have gender-affirmation surgery more than two decades later. “She thought that feminising her body might, to some degree, calm her inner conflicts without the finality of surgery; it was what she saw as ‘a half-way solution… better than nothing if less than enough,’” writes Clements. “During this time, Morris hid nothing of her dilemma from Elizabeth, who was already well aware of her spouse’s desire to transition…. In her autobiographical writing, Morris described their union as an ‘open marriage,’ suggesting that Elizabeth accepted her complex gender identity and that, as a couple, they had not always been monogamous.”

4.

A traveller can be thoughtful about their reactions to a place without pulling punches. “One of the skills Morris demonstrated was in comparing countries and cities. She believed that, in many Commonwealth areas, the barriers [of racism and social class] were coming down, but not in Australia. She was dismissive of the attempt to pursue an ‘Australian Identity,’ which she termed ‘a chimera.’” She wrote of Sydney: “For most Sydney citizens the purpose of life may be summarised in the parade of the life-savers on Manly Beach, all bronzed open-air fun on Saturday afternoons, and perhaps it is this paucity of intent, this lack of lofty memories or aspirations, that make this metropolis feel so pallid or frigid at the soul. This and what seems to be a shortage of kindness…. Compared with the great immigrant cities of the New World—Montreal, New York or São Paulo—this place feels cruelly aloof.”

5.

When discovering a destination, a traveller should pursue their own passions, not what they’re expected to see. “She pottered around junk shops and bazaars, delved into enchanting courtyards or ancient cemeteries, explored the riverside, quays, or sailors’ quarters around Docks, or idled away hours reading the local newspaper in fin de siècle cafés…. Museums and art galleries, meanwhile, were places Morris generally ignored, disdaining heavily trafficked sites in search of local colour. She favoured visiting a barber or a dentist, sitting in on court proceedings, or meeting the editor of the local newspaper. She once took in a children’s puppet theatre in Leningrad,” writes Clements.

6.

Don’t be afraid to be a trailblazer. Although Morris started hormone therapy in 1964, it wasn’t until the early 1970s that surgical transition seemed possible. “While cultural and social barriers around sexuality were beginning to be dismantled in the 1960s, little was known about gender identity,” writes Clements. Red tape interfered with Morris’s plans to have the surgery in the U.K., so she opted for Morocco in July 1972. “For a travelling writer, there was nothing unusual in Morris leaving her family to reconnoitre fresh territory. But this departure was unlike any other trips. At the age of 46 and after 23 years of marriage she was about to embark on a strange, bold, and lonely journey into the unknown.”

7.

A traveller shouldn’t be afraid to retrace their steps, but one should be more careful about doing so as one gets older. Morris continued to travel and write about her travels well into her 80s. “Being a traveller of a certain age now brought a special piquancy to her reportage. ‘The Big Trip’ was a pun at her own expense: while wandering around cities, she had become prone to minor falls. On a visit to St. Petersburg in the 1990s, she fell while walking the streets in the footsteps of Dostoevsky: ‘It was muddy and slushy, and I slipped in the Hay Market and lay in the street for a moment, rather shaken. Never fuss! Bruised and filthy as I was, I was cheered up when I realized that at almost the very same spot, the murderer Raskolnikov had kissed the ground of St. Petersburg in the last pages of Crime and Punishment.’”