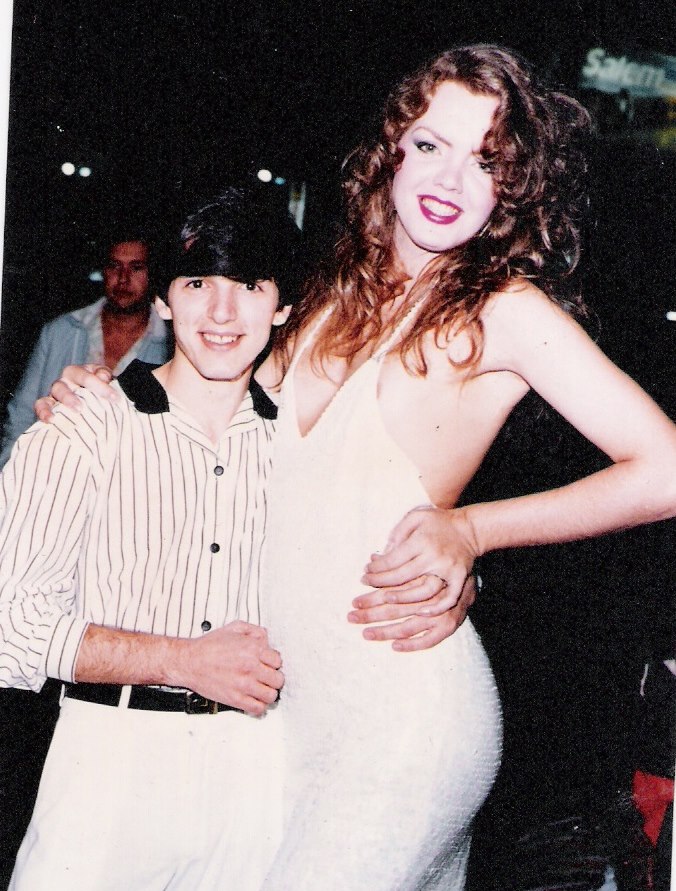

In the early 1980s, having grown up in a small town in Brazil’s interior, Zeca Prudente arrived in São Paulo, the country’s main economic hub, with the dream of becoming an actor. But as fate would have it, he ended up with a career in music. In 1985, at the age of 19, he was already the main DJ at the Nostro Mondo nightclub, considered the most important and longest-running gay nightclub in the country, open from 1971 to 2014. In those years, it was common for gay nightclubs in São Paulo to have not just dancing but also musical shows with dancers and queers lip-syncing, comedy shows, contests and talk shows. (Some even served dinner.)

Prudente’s early success, paid in dollars, came at the apex of his youth. He made several trips to Europe to have fun and buy vinyl records to play, at a time when many dance records and pop songs were not being released in Brazil. On his trips, he enjoyed the gay nightlife in Berlin, Paris, Rome and Brussels during a time marked by historic changes such as the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

Prudente also experienced the splendor and decadence of Brazilian gay nightlife during those years, as well as the peak of the HIV/AIDS crisis, which resulted in the loss of many of his friends.

In the 2000s, after a career spanning almost 20 years, he set the turntable aside to devote himself to his long-held dream of becoming an actor and producer, and established the casting agency ZP Actors, which he runs to this day. When Prudente is not working, he spends his time with his son (an offspring he didn’t find out about until years later) and grandson. He is currently writing a book about the Nostro Mondo, with testimonies from drag queens and trans people who were part of the São Paulo scene in the ’70s and ’80s. The book, entitled Nostro Mondo: The True Story, is due to be released in 2024.

How would you describe your life working as the main DJ in São Paulo’s most prestigious nightclub? It sounds intense.

I came to São Paulo in 1984. For someone who came from a small town like me and suffered a lot for being gay because of the family and the whole town, growing up was a horror—so here was a liberation for me. When I arrived in São Paulo, there was still a dictatorship [Brazil was run by a military dictatorship from 1964 to 1985]. The police were chasing us, waiting at the doors of nightclubs to beat us up. But even so, the ’80s were a milestone in my life, as were the ’90s—two very important decades. I was lucky enough to work at Nostro Mondo. I started out as a valet and bartender, and there I began my career as a DJ. I was the only DJ who earned in dollars in the ’80s, so I didn’t go to the other clubs, even though I still got offers to earn three times as much. I did play in other clubs later on.

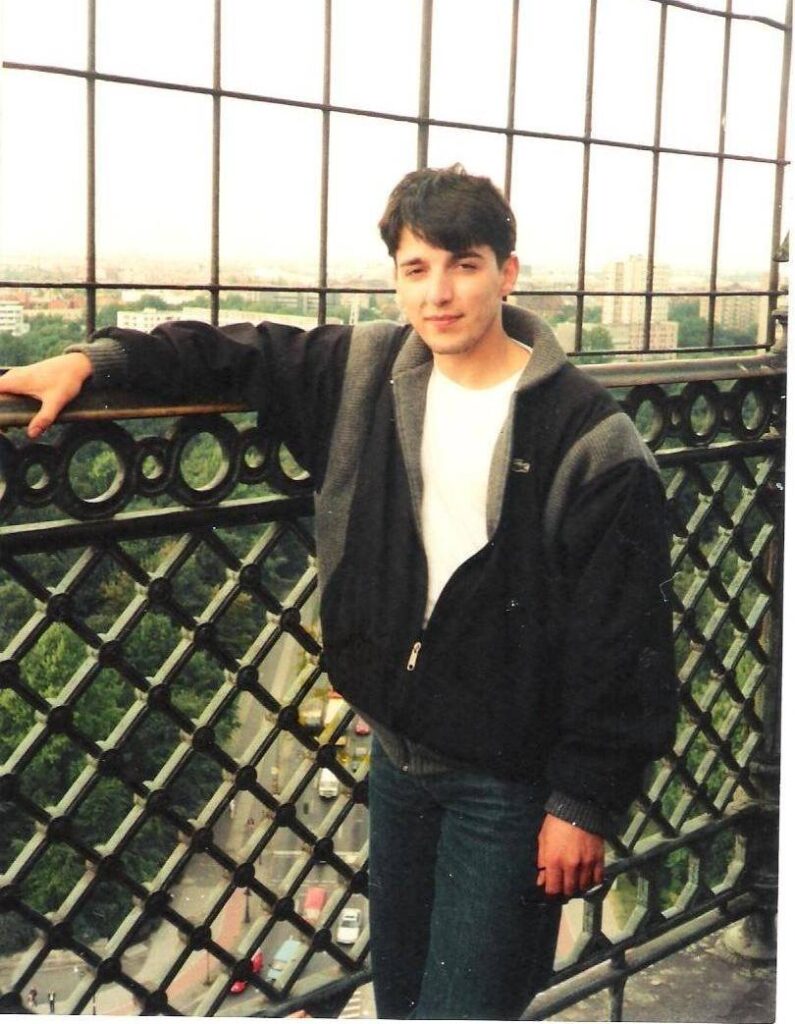

You quickly achieved success as a DJ and started travelling to Europe. Were these trips to buy records to play here or just to enjoy those places?

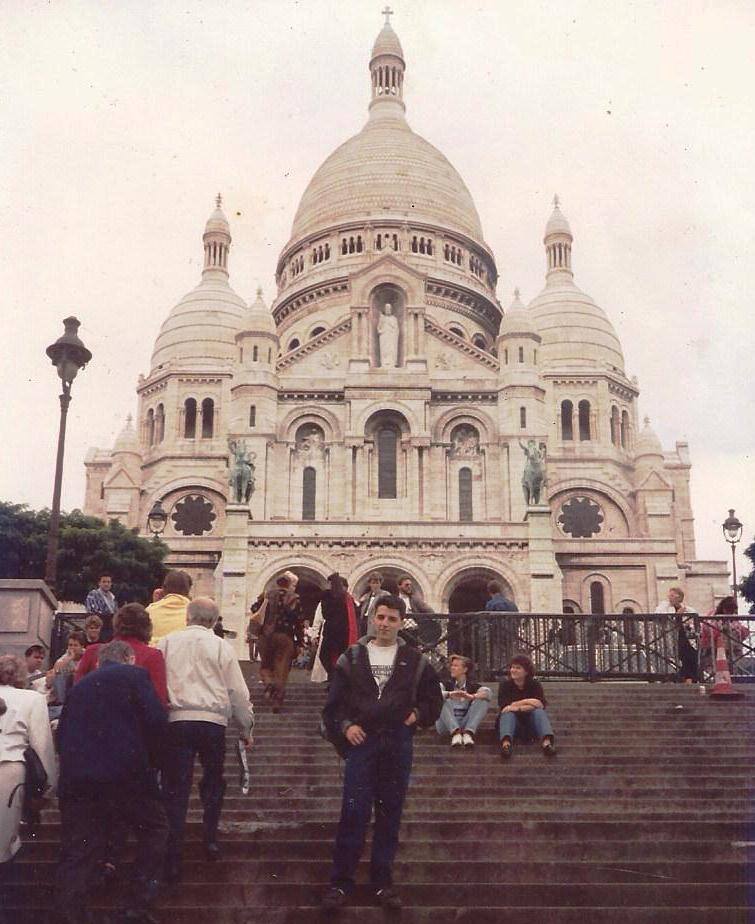

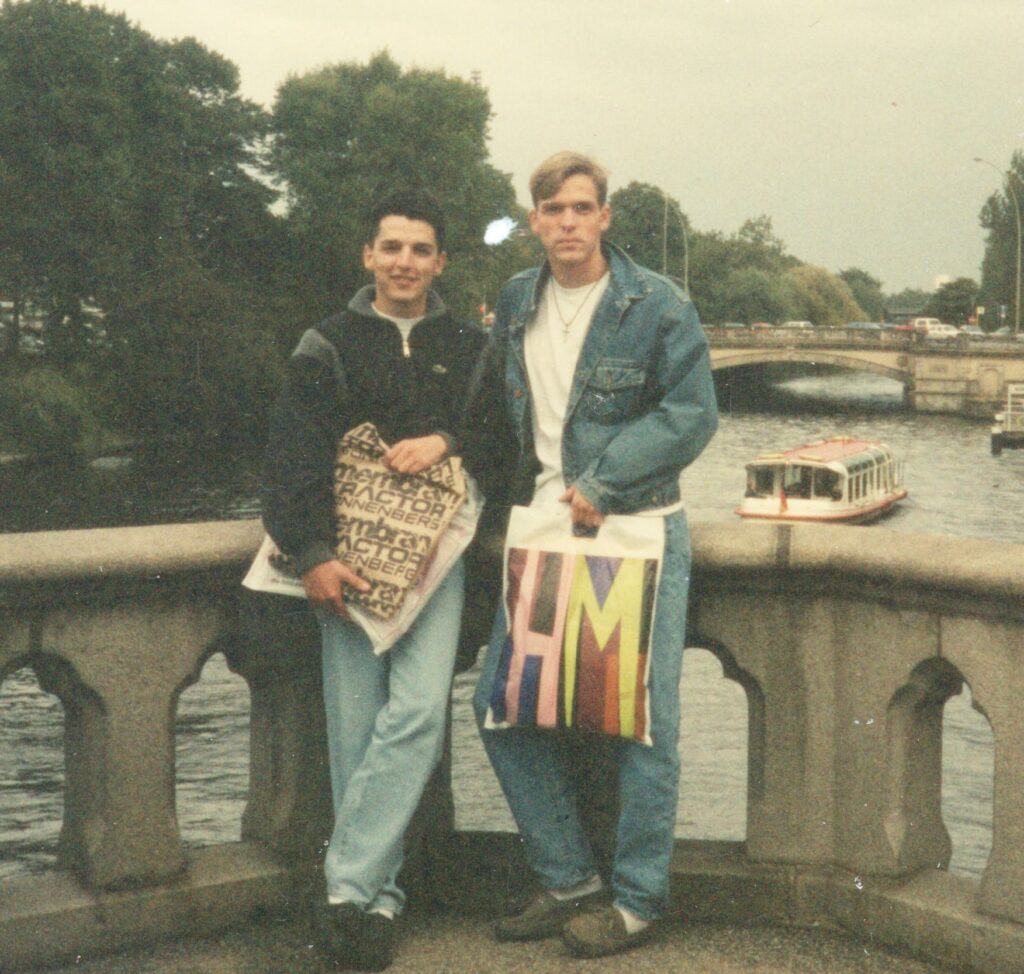

The first trip was to Germany in 1989. I spent a month travelling. I went to Hamburg, a city I recommend, then I went to Frankfurt and Berlin, where I saw the first gay shopping mall I’d seen in my life. I remember being shocked. In the 1990s, I lived in Italy for two years. I went to many places. It was impossible not to fall in love with Berlin, Rome, Paris, Brussels or even Buenos Aires, Argentina. The first time I went abroad I brought a lot of records—nobody knows this, but I brought the single by Technotronic to Brazil and was the first to play “Pump Up the Jam” here. I brought a lot of records from there, sold a lot of them here, and practically recovered the cost of the trip. I went to Argentina about 20 years ago; I wasn’t even playing anymore, but I still brought back a lot of records because there were a lot more released there than in Brazil, especially singles, and they were cheaper. My aim was to visit places, get to know different languages. I’m very good at learning languages, so much so that I learned Italian very quickly, and I would have learned German if I’d stayed longer.

What’s this about a gay German shopping mall in the 1980s?

It was a complex of stores of all kinds: sadomasochism, gay sex stores, bars, coffee stores. I can’t remember the name.

How did you discover Technotronic, and did you realize the music had the potential to be successful in Brazil?

The first time I went to Europe, I went to very few museums, more to record stores. [Laughs.] My ex-boyfriend argued with me about it. On the way to the airport in Hamburg, there was a record store called World of Music. I asked the taxi driver to stop at the store first, and I bought some records by Erasure, who had released some new remixes. By chance, I saw a cover that had a beautiful Black girl on it: Technotronic’s “Pump Up the Jam” single. I’ve always had a good ear, so when I heard the song, I said to the sales assistant, “I want 15 of these.” It was all the money I had. My ex got furious and argued with me in the store, saying I shouldn’t buy them. I said, “I’m going to take them, and I’ll be the first to play them.” It was a tremendous success in São Paulo.

What was gay life like during your travels at the time?

I didn’t go clubbing in Berlin. We walked around a lot during the day and were tired at night; the Berlin Wall was still up at the time. I saw more of Hamburg’s nightlife. There was a nightclub in the basement of a very old building that had an alternative sound that I had never heard before. I also visited the red-light district of St. Pauli in Hamburg; these were streets with prostitutes and rent boys in shop windows. And there were some love shows, too; you went into a booth, put in a ticket, opened the door and there was a mattress spinning with a couple having sex, like in that Madonna music video, “Open Your Heart.” I visited Italy’s gay nightlife in the ’80s and ’90s. By 1 a.m., everything closed down, no matter how crowded it was. The sound was turned off, and the lights came on. Once, I was in a nightclub in Monza, and I met a handsome Italian. We were talking, and when I was about to kiss him, the lights came on, and I asked him what had happened, and he said, “They’re closing.”

Can we say that it was easier to be gay in Europe than in Brazil at that time?

There is the good part of the story, the end of Brazil’s dictatorship, but I don’t want to praise it so much because it still wasn’t easy being gay. People thought they had the right to beat us up, as they still do today. The difference is that today there are laws. In the past, if I had been beaten up in the street like many of my friends were and went to the police station to report it, I would have been arrested for vagrancy and beaten up by the police. I saw a big difference in Germany. It’s a country that, compared to others like Brazil, has been further ahead when it comes to the LGBTQ community. In the 1920s, there were already gay balls and theatres there—Berlin was considered the gay capital of Europe. Great artists performed there, but that was before the Second World War; Hitler closed everything down. Even when I went in the ’80s, there was more respect. I saw gay couples walking hand in hand, kissing—something that if you did here in São Paulo in the ’80s, you could have been killed.

Have the places you visited changed much since then?

I returned to Italy in 2008 and went to a few gay bars in Rome. I don’t know if it was because of the Vatican, but they were still closing early.

What motivates you to travel these days?

I was going to travel in 2020, but the pandemic came, I had a heart attack, the pandemic ended, I had another heart attack, and I had to postpone it. I plan to travel next year, to Portugal, Italy, where I have relatives, and to Switzerland, where my sister lives. I want to get to know more cultures, and of course, if I find a record store there, I’ll buy some.

What are some funny things that happened to you when you were travelling as a young gay man?

In that nightclub I mentioned in the basement of a building in Hamburg, the staff didn’t communicate with the customers and didn’t even smile. To buy a ticket, you had to indicate the number of tickets you wanted with your fingers, and by carelessness, I showed my middle finger to indicate one. The German attendant grabbed my finger furiously and almost broke it. My German-speaking friend explained to him that I was a foreigner and that it was a misunderstanding, but we were almost prevented from entering the nightclub because of it.

Let’s talk about LGBTQ+ nightlife in São Paulo. Do you think it has changed much over time? Are there any options nowadays?

It’s changed a lot—it doesn’t compare to what it was like in the ’80s and ’90s. Back then, I couldn’t list the number of bars, saunas, nightclubs. It was something totally different. The nightclubs even had featured plays; people were astonished by all the luxury and wealth. Today, that’s unthinkable. A gay man won’t stop dancing to watch a drag queen perform or to see a star in a show with dancers. There’s no comparison in terms of quality and quantity today. São Paulo’s nightlife in the ’80s and ’90s was considered one of the best in the world. Many foreigners went to Nostro Mondo and other clubs.

Does this mean that there are no longer any cool places that could transport an LGBTQ+ person back to those days?

Nowadays, the most-established clubs are Tunnel (Rua dos Ingleses 355, Bela Vista, São Paulo), where a lot of young people go and which I think is a good place, and Blue Space (Rua Brg. Galvão 723, Barra Funda, São Paulo). The latter still has shows, but not as big as before. SP’s nightlife used to be unique, employing thousands of people—not just DJs but dancers, set designers, costume designers, waiters and clubs that served dinners.

You saw the impacts of Brazil’s HIV/AIDS epidemic up close. What was that period like? Do you consider yourself a survivor? I know you took care of many gay men and trans women until their last moments, after their families had abandoned them.

When a lot of gay people started dying, a sensationalist Brazilian newspaper published an article using the term “the gay plague.” We were blamed for AIDS. We got used to going to funerals; I used to go to three or four funerals a week, and the week there was no funeral, we’d say, “Oh, there was no funeral, nobody died.” That phase of AIDS was very difficult. I arrived in São Paulo in 1984, when it exploded. I can say that I was very lucky, especially to have survived because there was no treatment like there is today.

Tell us a bit about the book you’re writing.

Since I already write plays, I wanted to tell this story. I had planned to tell it from my point of view—everything I experienced at Nostro Mondo, all the confusion, the glories. I thought I’d write it all by myself. However, I decided to pay homage to the artists who are still alive, drag queens and trans people who performed. So I’m finalizing the interviews for the book and I’m in talks with a well-known publisher in Brazil. A screenwriter is already interested in turning the book into a streaming series. The book is tragic-comic; sometimes I’m writing it and I cry, sometimes I laugh. I can’t wait to release it.

This interview was conducted in Portuguese and translated into English by the writer; it has been edited for length and clarity.