Marwan Kaabour is a graphic designer and artist who moved to London from his home country of Lebanon in 2011. Though he has worked on many interesting graphic design projects, including Phaidon’s visual autobiography of Rihanna, he yearned to work on projects that had more personal meaning to him, as both an Arab and a queer person. In 2019, he founded the Instagram page Takweer to facilitate conversations about Arab culture and history from a queer perspective. The language and words people were using in the comments and in DMs ranged widely from dialect to dialect. Kaabour started gathering the words and expressions that spoke to the richness of slang and expressions used by queer Arabs, building a spreadsheet that eventually became The Queer Arab Glossary, which brings together queer words and expressions from across the Arab world.

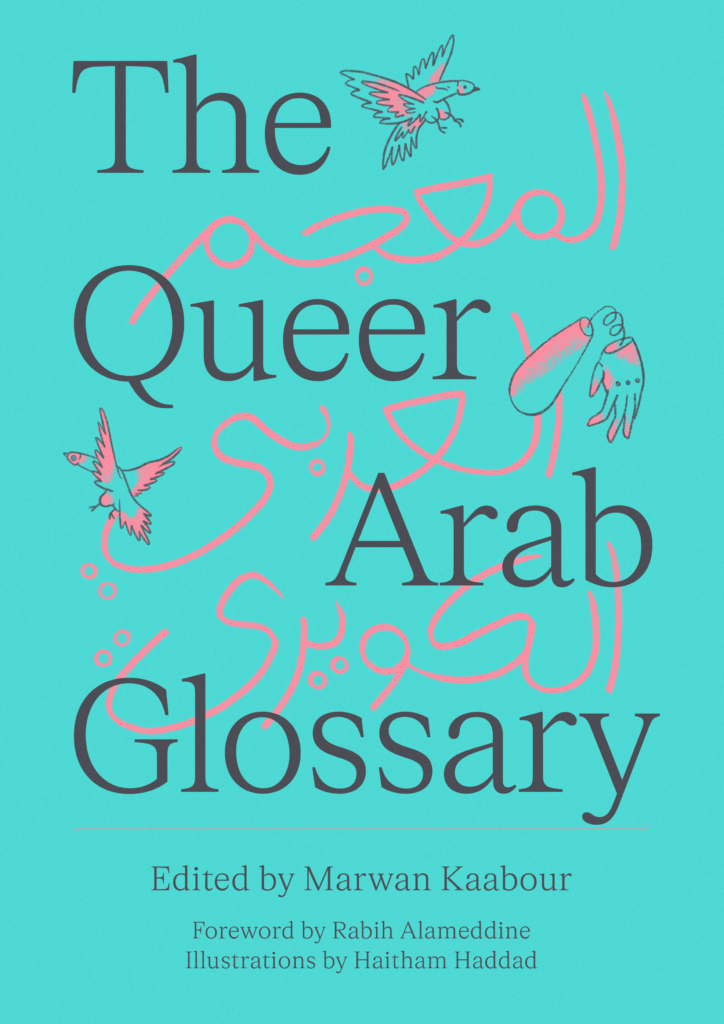

As the editor, Kaabour gathered words from Takweer users, then interviewed hundreds of people across the region, gathering more words and finding consensus on what each one meant, and how its meaning shifted depending on place and context. He found “Immī/Immé,” which literally means “mum,” used to as a term of kinship for a queer matriarch; and “Maftūḥ,” which literally means “opened,” used to describe someone who has been penetrated, that is, a bottom in gay sex. That’s not to be confused with “Mfaḥḥlé,” the feminization of the Arabic word for stallion, which refers to a woman with “manly” mannerisms. Illustrations by Haitham Haddad give the glossary a playfulness and a sense of delight, making even derogatory terms seem innocuous and perhaps empowering.

Pink Ticket Travel interviewed Kaabour about the glossary. Though it can be tricky for visitors to dabble with local slang—context and tone dramatically affect what things mean—travellers will surely benefit by knowing that such slang exists, what’s derogatory and what might very well be a pickup line.

I want to talk to you about the book and the assortment of queer expressions in Arabic that it covers. But I don’t think we can ignore the violence in the Middle East right now, particularly attacks on Lebanon. As someone who is originally from Lebanon, now living in London, I want to ask you how what is happening is affecting you. More specifically, how does it change the place of The Queer Arab Glossary in the world and how you see the project?

It’s absolutely devastating to see your home and your loved ones being put through so much terror. It feels very scary. I started working on the book four years ago, and I signed with my publisher in the early summer of 2023. We agreed on the release date before we knew of any of the violence that we are witnessing in the Middle East right now. There’s how you envision a project, your desires and ambitions for a project, and then there’s the real-time circumstances into which that project is born. My book, which is an exploration and celebration of the slang and language of queer Arabs across the entirety of the region, was born in a moment when my people, specifically Palestinians, Lebanese, Syrians, Yemenis, Sudanese and so on, are being exterminated.

Every single discussion I have about the book has to be rooted in this moment that we’re living in. I cannot sit here and talk to you about representation and inclusivity, about celebrating our voices and making sure our story is heard, when on the other side of things, we are being killed. Not by what the boogeyman that the West keeps propagating—our supposedly backwards homophobic leaders and communities. It is by the West, which is killing people on one side and talking about human rights on the other. It’s a very conflicting, very strange position to be in. But if I want to draw parallels: This book aims to archive and keep a record of a people whose voice is often marginalized and silenced, and that applies to Arab communities in general. It is a work of defiance to make sure that these voices, whether you like them or not, remain heard. While I travel the world promoting this book, it is to humanize my people, and to remind people around the world that we deserve the same space as everybody else—too many of us seem to have forgotten that.

Where did the idea for the book come from?

I founded the Instagram account Takweer in 2019, as a platform to collect my thoughts and explore ideas that are of interest to me, specifically in regards to exploring, documenting and celebrating queer narratives in Arab history and pop culture. The page serves two purposes. The first is an open-ended archive where I dig through my own history and try to find instances where queerness came to the surface. I then researched this, contextualized it, wrote about it and shared it back on Instagram, bilingually and for free, in order to create a sense of community and history, primarily for queer Arabs who follow the account. The second purpose is as a platform, a springboard for projects, of which The Queer Arab Glossary is one. On Takweer, a lot of interactions started happening with fellow queer Arabs from across the region, many of which have very different dialects. Those interactions would happen via DMs or in the comments, in Arabic slang. They would sometimes use a lot of slang that I was not familiar with. I developed a curiosity to know more, so I began asking followers to submit words and terms that they use or are familiar with. I started populating spreadsheets. I didn’t know precisely what the final shape of the project would be, but that’s how the database started to grow.

You mention that some of the dialects in the book are not your own. How much have you travelled around the region, and how much did you travel to research the book?

I’m very familiar with the Levantine dialect, which would to a large degree be spoken by Syrians, Palestinians and Jordanians. Egypt is a huge cultural player in the region—I’m very familiar with that language and dialect. I was less familiar with the other regions, whether North Africa, Sudan or the Gulf. The first phase of research was virtual field research. I then spent a year and a half interviewing people one-on-one from each of the Arabic-speaking countries, sometimes in person, sometimes virtually. I had the chance to have in-person discussions on several occasions in Lebanon and Morocco. From each country, I made sure the people I spoke to were of different ages, from different regions and socioeconomic classes, and identified differently when it came to the broad queer spectrum. I’m based in London, and I have a very wide network of fellow queer Arabs from different regions that participated.

I love glossaries, though for some readers they can be dry. But you have these playfully queer illustrations by Haitham Haddad that make this book both funny and pretty.

To subvert the glossary, and maybe the hurtful nuances that exist in many of the words, we used illustrations to create these almost-mythological creatures, to populate the queer Arab consciousness with our own version of fairy tales, super heroes, kings, queens and villains. A multiplicity of very different people occupying very different personalities. They’re not all super positive, but they’re all at ease with themselves, despite the contradiction. That’s the duty of these illustrations.

The glossary draws from various dialects. What are some of the common denominators and stereotypes that you found that fed into the language used to talk about LGBTQ+ people?

So many of the stereotypes about men, on an international level, are that you walk funny or you talk funny, or you act like a girl, or you’re girly or you’re sissy. So most are a reflection of a misogynistic and patriarchal society. Some of the most common metaphors are the use of water as something fluid, something that describes someone who sways or walks in a loose way. Metaphors like, “he’s fluid,” “he’s been touched by water” or “he’s diluted.” Words that pertain to men predominate, with a much smaller percentage pertaining to queer women. Whenever there is acknowledgement of a non-normative or queer woman’s presence, it’s always in the context that she’s a man. She’s like a boy, she’s a tomboy, she’s trying to emulate a man. It’s never about her own experience.

There’s another metaphor that I found peculiar, across all six dialects, and that’s the metaphor of worms. “The one with the worms,” “riddled with worms,” “having a worm up the butt.” I’m translating, obviously. The Arab region is massive, populated by over a billion people, and the linguistic influences that make up our regional dialects are equally massive, so it was surprising that such a specific metaphor and its association with being gay or a bottom, or being effeminate, seems to have travelled throughout the entire region.

You don’t separate nasty insults from words that might be used by the queer community more affectionately. You have the affectionate Gulf region word for twink, “Faṭfūṭ,” on the same page as “Shādhdّh.a,” an offensive word for deviant. Why did you do that?

In the beginning, in the spreadsheet where I was collecting my research, I had, in addition to the word, its meaning and the place where it was used, two columns: “derogatory” and “endearing.” I wanted to categorize these words, or to add a legend, to note which were derogatory and which were endearing. I quickly realized there is no way, except in very exceptional cases, that you could make that distinction in such an explicit way, because the meaning of a word is defined by who says it, to whom it is being said, in what context it is being said, the point in history in which it is being said, in which locality it is being said and tone of voice. All of these factors create the meaning of a word, and I have no authority to make that decision on behalf of a people. Instead, in some of the entries, I’ll say if it’s primarily a derogatory term or primarily an endearing term. I opted to provide as much nuance as possible and leave it up to readers to position themselves in how they feel about each word.

How useful would it be for a visitor to know some of these words?

Language is complicated. We all have our own relationships with words that might be rooted in specific memories or events, that might make us laugh or cry. So I think the glossary will ultimately trigger a range of emotions, but what I do hope primarily is that it empowers queer people—specifically, Arabic speakers—to engage more closely with their own language instead of falling back onto English when they want to talk about their sexualities or their identities. In the region, we do tend to do that—as soon as we want to talk about being queer, about our sex lives or about our sexuality, we start using Western terms, because the distance puts us at ease. What I would like to do with this book is switch that relationship around and start the dialogue in our own language, to begin a process whereby we can start using our language in a more endearing way, one that puts us at ease and more in touch with the culture that we were born out of.

The book certainly gives us lots of examples that homosexuality and queerness have been talked about in Arab cultures for centuries, at all levels of society. It’s a matter of owning it.

It’s a ridiculous statement to say that queerness is a Western import. History speaks for itself. We can go back to One Thousand and One Nights, a collection of tales [dating back to 600 BCE] that wasn’t originally in Arabic but was popularized in Arabic. It was filled with sexually explicit stories of orgies and gay sex and lesbian sex and people having sex with mermaids and eunuchs. It was so wonderfully explicit that when it was translated into Latin languages, Europeans were shocked by how morally depraved the book was. The point I’m trying to make is that the world always seems to be in a collective state of amnesia, that we’re only willing to remember the state that we are in from, being generous, 50 years ago, and we don’t bother to actually look into our own history. The language around queerness has existed as long as the Arabic language itself. It is also a challenge to Eurocentric and Western discourse that proclaims that Arabs or Muslims or the people who live in that region are somehow born homophobic or sexist.

Do you have some few favourite expressions that you’ve gathered, maybe even derogatory ones that you think are clever?

I love the term “Shawwāya,” which is from Tunisia. It means a grill rack and is used to refer to a gay person who is versatile, because just like meat on a grill rack, you need to flip them over every now and then. There’s such wit in that. I love it. There’s a term from Morocco, “Qāyiso-l-mā,” which means one who has been touched by water, which I discussed earlier. It’s derogatory, suggesting gay or queer men are loose, swaying as if they’re liquid. But there’s something so beautiful about being touched or baptized by gay water. You can bask in the glory of it rather than it being a source of shame.

You’ve been on a multi-continent book tour. Have you learned things about yourself on your travels?

I can confidently say that I did not know this before, but I seem to be an excellent public speaker, which is something people keep telling me. So now I just have to accept it. I’ve enjoyed speaking with people and having dialog in a public forum.

Do you have specific needs when you travel, certain things you want in your hotel room, maybe a bowl of candy backstage before you go on?

I haven’t been asked for a rider just yet. Give me a year. But I love hotels and I love airports, which is a weird thing to say. Airplanes, airports and hotels are spaces that exist in limbo—you’re neither here nor there, you’re in this space of being in between. These spaces, once I’m through security, put me at ease. I do need a good mattress, good pillows.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.