U.K. artist Claye Bowler is probably one of the most organized artists you’ll ever meet. He keeps track of his past shows and his ideas for future projects in a spreadsheet, and writes down his comings and goings just in case something later becomes useful to their art. “I’ll ask myself, ‘Oh, what was that place I went to that one time 10 years ago?’”

Top, Bowler’s recent show at Queer Britain (2 Granary Square, London), takes the form of a museum store to introduce viewers to an archive of his seven-year journey through the U.K.’s healthcare system to access gender-affirming top surgery. Each piece in the installation—objects, letters, films, sculptures—is carefully displayed and documented. But the result is not dry—the show has real emotional resonance.

Pink Ticket Travel caught up with Bowler to talk about the feedback from the show, his favourite places to visit and how he deals with the anxiety of travelling while trans.

You showed the exhibit Top at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds in 2022, so the Queer Britain show was a bit of a replay. How was it different the second time around?

The Henry Moore Institute is a contemporary art venue, but also quite academic. They do a lot of research, so it was viewed there through an academic art lens. The Queer Britain show was in more of a community DIY space, so the audience was younger, people just getting into museums, new to the stuff. I had been making all this work about getting top surgery, and I had these objects and images and sculptures and films and things. I had made a spreadsheet archive of everything that I had, like: What can I put in this exhibition? Then I realized that the exhibition was the spreadsheet. It was the whole thing. Queerness isn’t in these museum archives, these spaces—a lot of the queer aspects of objects get taken out of them. It gets hidden. The exhibition is about the lack of queerness in the museum and archive world, referencing queer museums, so for it to be in a queer museum, it’s quite relevant.

You’ve had so many exhibitions in so many places lately that you mentioned on social media that you feel like a musician on tour.

I showed Dig Me a Grave, the show I had at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park (West Bretton, United Kingdom), twice before this year, in London and in Cornwall, so I’ve been travelling with that. There’ve been other, smaller shows, so it’s been, I think, 14 this year. I had three years of not showing any work, then suddenly this. I feel like it’s the same with touring musicians: they bring out an album and tour the album, and then they’ll go and be a recluse and think on the next album. I’ll often spend a whole year just absorbing things—travelling, visiting exhibitions, talking to artists, reading, watching documentaries—until I have an idea for the next work.

You need to get yourself a Claye Bowler tour bus.

That’s the dream.

Your first group exhibition was almost a decade ago, and you’ve been documenting your transition since around 2016. Your transness and your art career seem to be very closely tied.

The Top exhibition at Henry Moore was the first time I’d had that much exposure. I didn’t realize how many people would then ask further questions. I felt like, here’s the work. Then people would probe more: What is this object and what does this surgery do and why do you feel like that? It was too much. I tried to take the transness out of my work after that show, but it’s impossible to do that. With Dig Me a Grave, it’s still about transness, but it’s not so overt. Maybe it’s about subliminally getting people to realize it’s about transness. So when they experience empathy for the work, then it’s like, haha, you’re now an ally.

Has touring the U.K. with your shows changed how you see the country?

I didn’t have a passport until I was 19. When I was a kid, when we went on holiday, it was always to various parts of the U.K., so I’ve always felt more connected to the U.K. than friends who went abroad. But I don’t feel tied to Britishness or any kind of nationalism. I like the familiarity of the British countryside. The U.K. at the moment is not great for trans people and it’s getting worse. I know people who have moved to Australia, and places like that. I use folk songs in my work because I like the ancient side of things—these songs have been passed down through people and no one really knows their origin. There’s a moral of the story that people read from them now, but we don’t know if that was always the intention or if the songs have been changed. Did it end differently before? I’m also interested in the countryside here and the carvings on Neolithic stones. People put narratives on them, but we don’t actually know what they mean.

What’s a favourite place to visit in the U.K.?

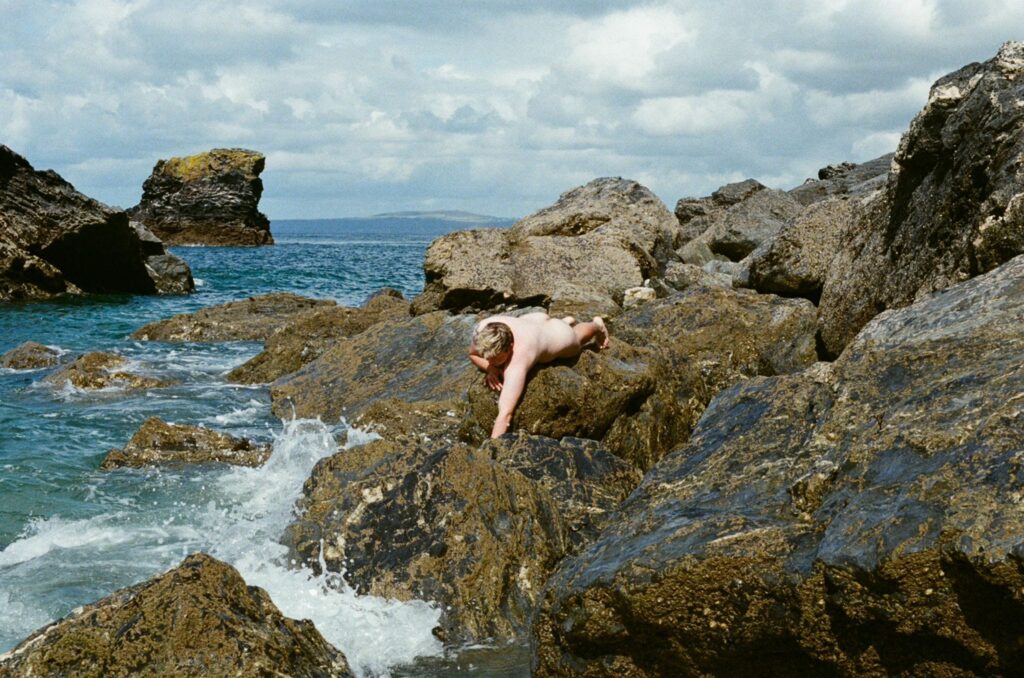

I’ve spent a lot of time in Cornwall over the last three years, so it kind of feels like my second home. It has a lot of pagan history and Neolithic sites, like the Isles of Scilly. It’s also got a lot of really good art and artists. Plus beaches and coves. There’s a different climate in Cornwall than the rest of the U.K.—there are tropical plants and succulents growing there. It’s this other world, but in a comfortable way.

They have the Tate St. Ives (Porthmeor Beach, St. Ives), which is a branch of the one in London, only smaller. St. Ives was where the famous sculptor Barbara Hepworth lived. You can visit her old studio, Barbara Hepworth Museum (Barnoon Hill, St. Ives), which is preserved as it was in the 1970s, when she died. There’s a sculpture garden you can walk around—it’s also part of the Tate. There are also loads of smaller galleries and studios like Auction House (Station Hill, Redruth), which is located in a small mining town. You’ve got Hweg (34 Causewayhead, Penzance; temporarily closed) and Tremenheere Sculpture Gardens (Nr. Gulval, Penzance). During the summer you can see a show at Minack Theatre (Porthcurno, Penzance), which is an open-air cliffside amphitheatre. There’s also a nudist beach at Pedn Vounder (S.W. Coast Path, St. Levan, Penzance).

What’s an international trip that made a big impact on you?

I lived in Iceland for two and a half months. I’ve been to other places in Europe and they’re kind of similar to the U.K., but Iceland has an entirely different landscape. I had never seen any of the plants there before. Or the rocks there and how it felt when you walked on them. I was there when it was sunlight the whole time, so it was like this weird energy where everything was bright and otherworldly.

When I go on holiday, I like to be more of a recluse and on my own. Because it’s so small, I feel like people do keep to themselves, but they’re also a tight-knit community. I prefer to be anonymous and on the outside, so I liked that about Iceland.

I visited Reykjadalur, a geothermal valley. I got there by bus, and then you walk through the valley with all this hot steam coming out of the ground. There’s a cold glacier river, which meets with a boiling thermal river. You can swim at a point where they converge. It’s the perfect temperature. I collected a lot of objects on that journey. I made an artwork from these rocks and stuff that I’d ground up into a powder, then made paint out of them.

When you travel, do you seek out other trans people? If so, do you have any strategies for finding them?

In Iceland, I did. Because I was there for a while, I found a trans support group. I met loads of people that way. We went for walks, went to the cinema, protested—things like that. I’ve met people on dating apps, especially in Iceland. I went on four dates there. I’m not sure if I would have done that if I was there for a shorter length of time. Usually if I’m on holiday, I need to see every art gallery in a city, so I don’t really do queer things.

For some trans people, crossing borders and visiting countries that may or may not be friendly can be a fraught experience. How do you deal with it?

I’ve never been to anywhere that is not great for trans people. The farthest I’ve been is Berlin and Switzerland. I often take the train, which means a lot less security. When you take the train to Europe out of London, there are no body scanners, just a metal detector. I prefer the train in general. But thinking of coming to America, I’m like, would I? Sometimes you catastrophize things, you have anxiety, and then it turns out fine. I’ve never really been anywhere that far.

As you become better known around the world, you may be invited to visit more countries.

If that happens, I’ll be working with a gallery and asking them, “What are you doing to make sure this is all going to be fine?” I’d make sure they were going to support me before I said yes. I’d put the onus on them rather than on me.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.