Queer Cinema World Tour is our regular feature taking you to destinations behind your favourite LGBTQ2S+ film moments. This week we visit the Pacific Northwest, the setting for 1991’s My Own Private Idaho.

One of director Gus Van Sant’s perverse jokes in My Own Private Idaho is that none of the movie takes place or was made in Idaho; the scenes on the highway which one might presume to be in Idaho—the road where the barn structure crashes from on high onto the pavement—were shot along Sherars Bridge Highway, Oregon Route 216.

It’s true that the symbolism of “Idaho” as a state of mind, as well as a trip to Rome late in the film, are very important for our protagonists, the narcoleptic Mikey Waters, played by the late River Phoenix, and the patrician Scott Favor, played by the now-megastar Keanu Reeves. But the film’s physical and spiritual home is in Washington and Oregon, where the light is almost always muted and misty. It’s a weird kinda guide to Portland LGBTQ travel.

The film kicks into gear as the two young men, working as hustlers in Seattle, meet cute in a mansion while in the service of a wealthy female client. The gig is a step up from the mean run-down streets of downtown where they are usually putting in their time. The Seattle hustler haunts of the Gatewood Hotel and St. Regis Hotel, which we catch glimpses of, no longer exist. Though the St. Regis site is now an apartment building, it might be a thrill for Van Sant fans to stay at the Palihotel Seattle, a modern-retro-cool boutique hotel which now occupies the 107 Pine Street address that was the Gatewood. It certainly offers a more cheerful well-crafted experience than the seedy 1990s Seattle Van Sant was conveying.

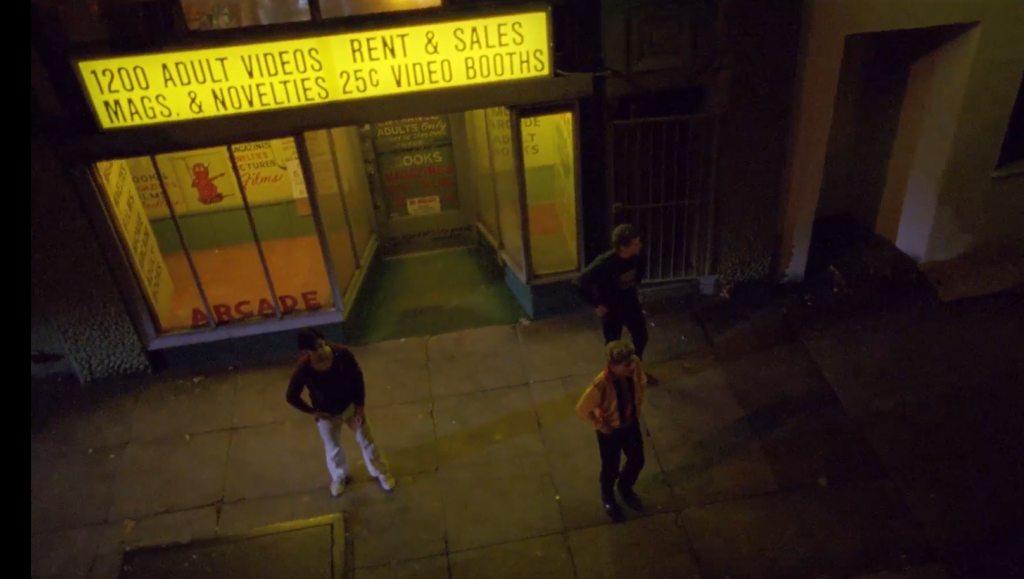

One of the film’s most memorable scenes, where models on the cover of skin magazines start moving and talking to each other, was shot at a porn store called Video Follies, which was on Portland’s SW 3rd Avenue; that building is gone, replaced by a mid-rise residential building.

Fans of My Own Private Idaho love to argue about whether Mikey and Scott are straight, gay, bi, gay for pay, asexual or something else. Van Sant leaves this open to interpretation. For the purposes of this tour, let’s presume the two are at the very least homo-social and while in Seattle spent some time in the Capitol Hill gaybourhood.

The two might have liked the classic spot CC’s Seattle (1701 East Olive Way, Seattle), which never charges cover, though it opened two years after the movie debuted. If Mikey survived into the 2000s, he seems like he would have been a gamer type and would pop round for Seattle Gaymers night every Wednesday. Mikey and Scott were also too early for the Cuff Complex, which opened in 1993 (1533 13th Ave., Seattle), though its hairy-leather-queer-dude vibe might not have been their scene.

A Seattle bar that the duo could have dropped by, since it opened in 1989, is Changes in Wallingford (2103 N. 45th St., Seattle). These days they’ve got a video DJ and classic video games for 25 cents a play, as well as a pool table, so a perfect spot to kill time waiting for the next trick.

The Seattle chapter of the film ends when Mikey stomps off from the advances of a perhaps-customer, a German guy named Hans played by camp icon Udo Kier, and has a narcoleptic episode in the middle of a residential area near W 8th Avenue at W Galer Street. The shots here have a foggy view of Elliott Bay. (Hans comes back a surprising number of times over the course of the film.)

Mikey wakes up cradled in Scott’s lap, sitting on the edge of Portland’s Elk Fountain (1120 SW 5th Ave., Portland), about 280 kilometres away from where he fell asleep. The actual statue is, well, just a statue of an elk, commemorating former mayor David P. Thompson. But for the film, Van Sant reportedly had one of his assistants painted green to sit atop of the elk, like it was being ridden, perhaps into battle, and added the words “The Coming of the White Man” to the base. It’s a serious layer of commentary to lay atop a beautiful mammal.

Our duo settle down in a squat with a group of other street-involved rebels at an abandoned hotel, the Governor, in downtown Portland. And do you know what? Van Sant was very good at picking scruffy old locations that have since been gussied up to become of interest to the modern-day traveller. Just like what happened to the Palihotel in Seattle, the Governor is, after a $6-million makeover in 2014, now the chic Sentinel by Provenance (614 SW 11th Ave., Portland), which has been suggested as one of the best places to stay in Portland for people who love nightlife. They donate a percentage of room rates to LGBTQ2S+ charities during Portland Pride, which takes place in July.

Another hotel our protagonists visit, The Imperial, is now Hotel Lucia (400 SW Broadway, Portland), another boutique property by Provenance, which has a playful decor and also partners with Portland Pride.

Okay, not all of Van Sant’s hotel picks worked out. The Thunderbird on the River Hotel (1401 N Hayden Island Drive, Portland), where Mikey looks for his long-lost mother, was closed in 2005 and destroyed by fire in 2012.

Portland, Oregon, is a very queer city, which we’ll cover in more depth another time. Regardless, Mikey and Scott were too wrapped up in their own traumas and dramas to watch drag shows or go dancing. The Portland Queer Comedy Festival, which takes place in July, and the Portland Queer Film Festival, which takes place in September, were likely beyond their interest.

Back in the early 1990s, they’d have been able to visit Scandals (1125 SW Harvey Milk St., Portland), which opened in 1979, and Silverado Nightclub (610 NW Couch St., Portland), whose history dates back to the 1970s, though with location changes and rebrands. The advantage of the Silverado is that, as an exotic dancer bar, Mikey and Scott might have been able to earn some cash here.

But would they want to? New since the era of My Own Private Idaho is the Portland Sex Worker Resource Project, which provides harm reduction supplies and supports specific to sex work. Perhaps Scott wouldn’t have taken advantage of their services—he married a woman and was set to inherit lots of money. But Mikey, last seen on Oregon Route 216, might have found some much-needed peer support with the project.