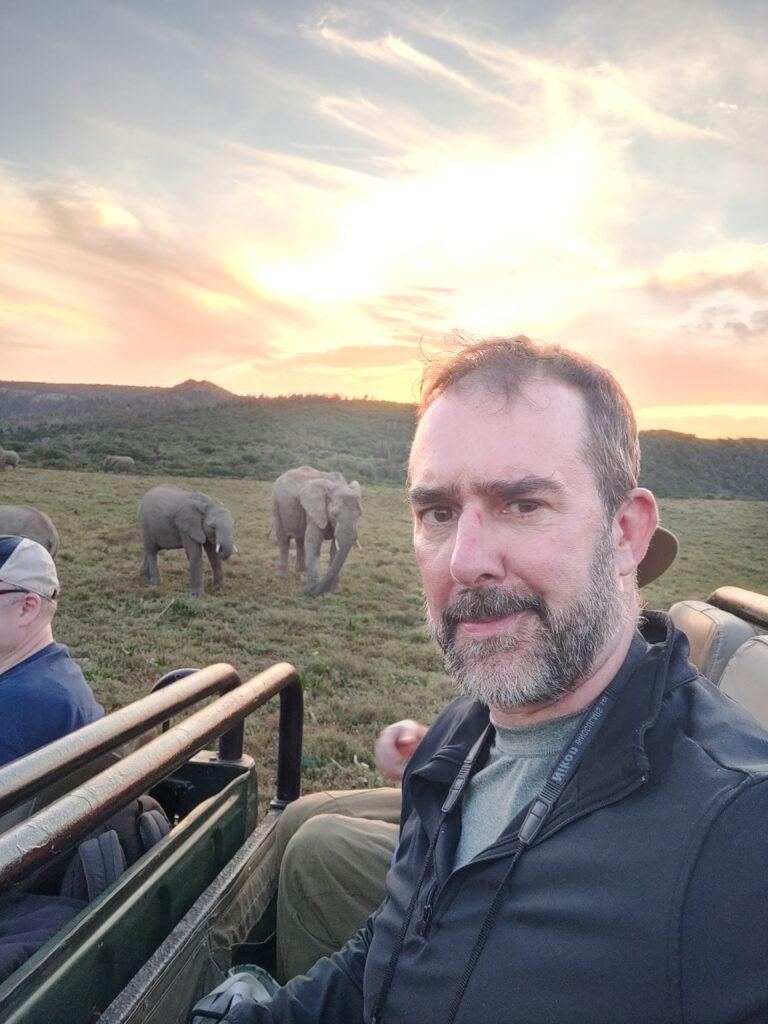

I had many worries about going on an African wildlife safari, but none of them included staring down a herd of irritated elephants in the middle of the night. Yet here we were, after dark at the Kariega Game Reserve in South Africa’s Eastern Cape, with about a half dozen elephants (that we could see) moving spookily toward our cruiser. I know nothing whatsoever about elephant behaviour, but the gurgling-grumbling sounds obviously didn’t mean, “A warm welcome to our corner of the jungle, dear friends.”

“We need to go,” our host said to our driver, who put the cruiser in reverse and navigated us onto a different trail. We drove through the thicket in the direction of our lodge, navigating the landscape of rolling hills around Boesmans River. The drive took almost an hour. There was a sense of relief when we got out of the cruiser and headed back to our suites for the night. But my own nocturnal adventures were not quite over. Driving my golf cart back to my suite along a dimly lit path, I startled a tower of giraffes, sending several of the huge creatures dashing down the path ahead of me. They went around the bend. So did I. It felt like a dream. When I arrived at my suite, the giraffes were gone. I was a little disappointed. It would have been nice to hang with them for a while. They have beautiful eyelashes and are known to indulge in some pretty gay activities.

Although most travellers going on their first safari fret about the dangerous animals—they want to see lions and leopards close up but are also terrified about getting too close—my worries going into the experience were much more prosaic and human. Not just: Would I be safe on an African Safari? But: Would I be bored, driving around looking for wild animals? Would it be hot and dusty? Would the food be okay? Would there be mosquitos? Would it feel like we were harassing the animals? Would there be a mess of looky-loos making the experience feel gross and exploitive? Would it be boring at night out in the wilderness? Also on my list: How LGBTQ+-friendly would the experience be?

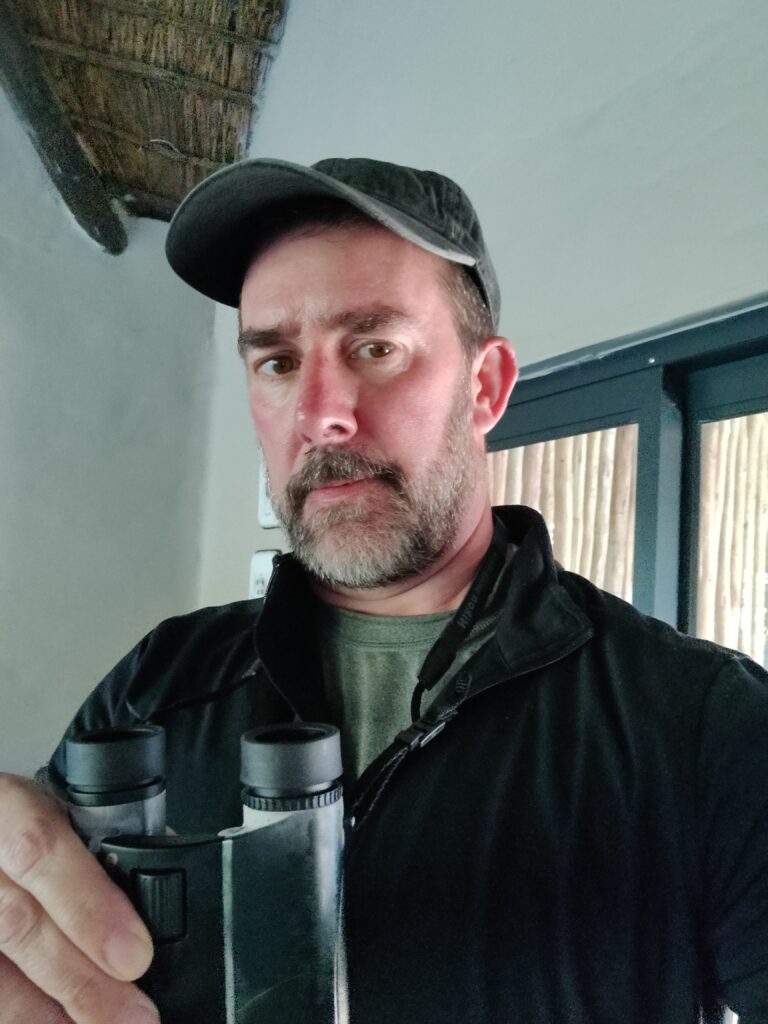

I was travelling as a single gay male traveller, so I didn’t have anybody to cuddle or hold hands with to test the acceptance of the reserve’s staff, our driver, our guides and other locals. I’m not particularly flamboyant (usually) or gender nonconforming. And I certainly didn’t want to purposely upset local sensibilities or push buttons.

But I had a few things to go on, starting with my knowledge of the socio-political context of South Africa. I knew that if I encountered a problem, the law was on my side—the South African bill of rights, which came into effect in 1991, is one of the world’s most progressive toward LGBTQ+ people. Discrimination and crimes motivated by homophobia are prohibited. I also knew that attitudes are welcoming. Because I had already visited two cities, Durban and Johannesburg, I had seen active and public queer communities in South Africa, and I knew that there were openly gay businesses and openly gay people working all across the hospitality industry.

Wildlife safari experiences, though, are located far away from cosmopolitan areas, where local attitudes might not be as friendly. Even if the law is on your side, who wants any shade while on an expensive holiday?

The thing I discovered is that visitors on safari often find themselves inside a travel bubble that has been put together by a tour operator with an eye to pleasing travellers from Europe and North America. These travellers may be visiting safari lodges and other vetted places but are probably not strolling around towns and villages. The tour operator can customize everything from transportation and accommodation to the meals and other experiences. By being thoughtful in their hires and contractors, an increasing number of operators are making sure their bubble is LGBTQ+ friendly.

There are, of course, commercial interests driving this, especially the perception that LGBTQ+ people are willing to spend more for travel experiences—and safaris are among the most “bucket list” of travel experiences. Locals who work in the safari industry are extremely familiar with international travellers and know that foreigners can be very different from themselves and from each other—in their dress, diet, daily routines or sleeping arrangements. Whatever locals think about these differences, they know that the spending done by these foreigners helps them make a living. In hospitality, part of the job is not to be too bothered by any paying customer’s beliefs, preferences or appearance. Practically speaking, making sleeping arrangements for, say, a blended family of seven is usually more of a bother than pushing two twin beds together. Not to sound like I’m upselling, but the more luxurious the experience, the more likely that staff and contractors are trained in inclusiveness and being accommodating to all guest needs.

Some operators see LGBTQ+ inclusion as not only a commercially smart move but also an ethical one, and will go further to implement inclusive standards, perhaps getting accreditation by an organization like the International Gay and Lesbian Tourism Association. One operator I talked to, Cape Town-based Springbok Atlas, is an upscale tour and safari company whose main client base comes from North America. The company is an IGLTA member and has to meet certain criteria of friendliness.

“We make sure we use venues and suppliers that are all LGBTQ+ friendly. We’ve got to know that wherever we’re sending travellers, they’re going to be completely comfortable,” says Springbok Atlas CEO Glenn McKeag. “We wouldn’t necessarily in all places be able to arrange gay guides or ensure that the rangers are from the LGBTQ+ community, but we can make sure that their expectations are met, whether it’s a group of friends or a same-sex couple on honeymoon.”

In South Africa, McKeag says this is pretty easy; inclusiveness is built into the culture. Even outside the safari bubble, he sees many LGBTQ+ travellers add on visits to Cape Town (read our insider’s guide here) and the wine region nearby, experiences where a tour operator can’t vet every receptionist, server, guide and driver but can be confident homophobia and transphobia will be unlikely. He recently organized a tour of Cape Town for a group of 55 lesbian and bi women from the United States “who broke this town down,” having fun all over the city.

Springbok Atlas also offers safaris in the Southern African destinations of Botswana, Mozambique, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe, each with its own distinct laws and attitudes affecting LGBTQ+ people. McKeag has seen attitudes improve in Botswana and Namibia. “Botswana especially does not so much as bat an eye when it comes to LGBTQ+,” he says. At the same time, their tours tend to bring visitors straight from the airport to the safari experience without stops in any cities or towns; the company may not be able to direct societal attitudes, but there are enough LGBTQ+-friendly suppliers available that they can make sure the experience is a positive one.

Zimbabwe, which criminalized same-sex sexual activity in 2006, is another story. Though the safari suppliers working inside the bubble have met certain criteria, it can be trickier to push boundaries when you know that the law is not on your side. In various online forums, travellers have shared advice suggesting it’s a wise idea to present as “buddies” in public and during group activities in Africa. Though nobody working in the hospitality industry should be putting your sleeping arrangements or wardrobe under scrutiny, it can be better to be ambiguous than definite. The other side of the equation is that what might come across as flamboyant or non-normative in some cultures can come across as enjoyably extroverted, or merely eccentric, in others.

The rest of my worries—harassing animals, too many other tourists, dust and boredom—did not come to fruition for the rest of our time in Kariega. All our outings were delightful and exciting, especially watching two young lions being summoned to a kill by an older female. (We didn’t see the kill, which was fine by me.) Our safari group saw several of the “big five” animals.

But it is the memory of giraffes running away from me in the night that I’ll cherish most. If giraffes could talk, I’m sure they’d have a few stories to tell, not all of them suitable for mixed company.

The writer was a guest of South Africa Tourism; the hosts of the trip did not direct or review coverage. The views expressed are the writer’s own.